By: Brent Parrish

The Right Planet

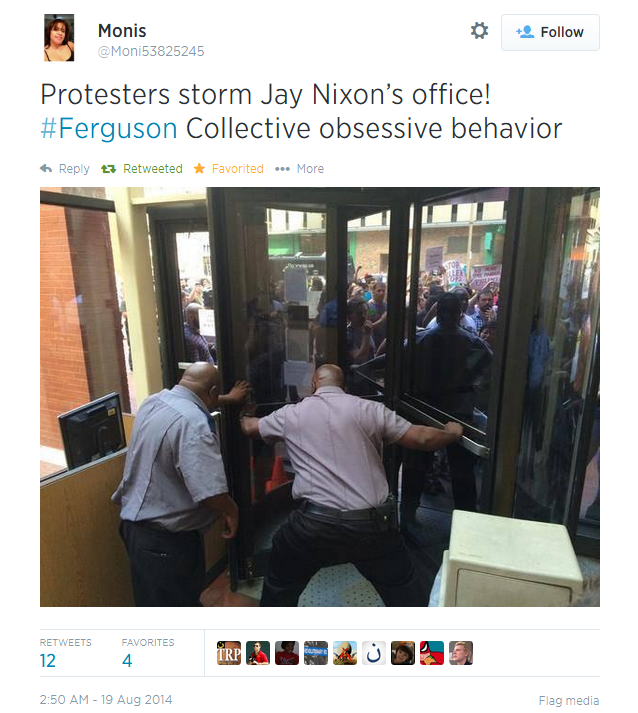

Our Founders called it “mobocracy.” And mobocracy is synonymous with democracy. But isn’t democracy synonymous with freedom? No! Not unless one defines “freedom” as mob rule.

It might surprise some to learn the United States is not a democracy. Article 4, Section 4, of the U.S. Constitution clearly states the United States “shall have a republican form of government.” Our form of government, as required by the Constitution, is a constitutional republic, not a pure democracy, despite what the so-called “constitutional scholar” who now occupies the Oval Office claims. (Barack Obama has stated in the past that the U.S. is the world’s oldest constitutional democracy, which is patently false.)

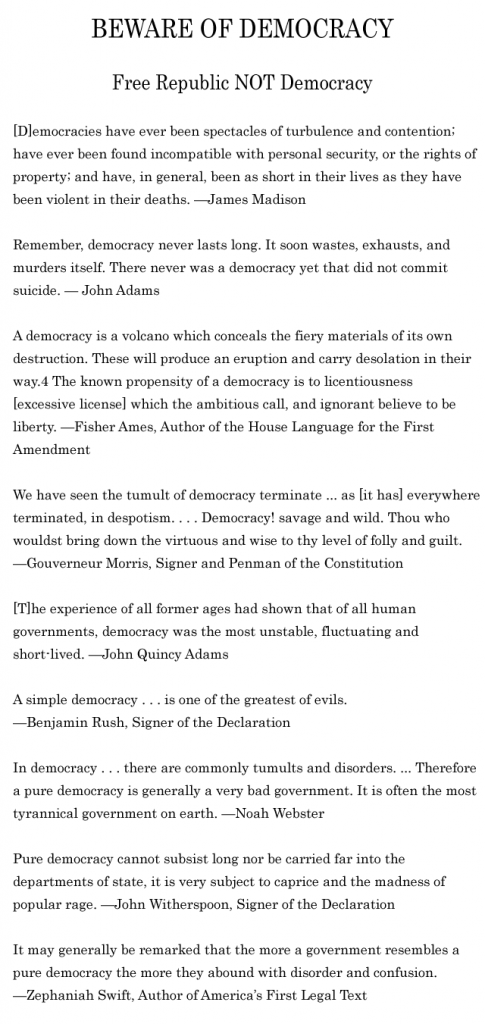

The Founders warned, from the very beginning, that pure democracy is one of the worst forms of government that exists. Pure democracy is simply the rule of the majority, i.e. mob rule. But a constitutional republic is based on the rule of law, which protects both the majority and the individual.

The Founders warned, from the very beginning, that pure democracy is one of the worst forms of government that exists. Pure democracy is simply the rule of the majority, i.e. mob rule. But a constitutional republic is based on the rule of law, which protects both the majority and the individual.

“Democracy is the recurrent suspicion that more than half of the people are right more than half of the time.”

—E.B. White

The term “democracy” does not appear anywhere in the U.S. Constitution, or the Declaration of Independence, or in any State constitution.

Even in the Federalist Papers, “democracy” is rarely mentioned. But there are a few places in the Federalist Papers where democracy is discussed–specifically, in Federalist Papers #10, #14 and #48.

On democracy, from Federalist Paper #10, my emphasis:

… From this view of the subject it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure and the efficacy which it must derive from the Union.

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended….

On democracy, from Federalist Paper #14:

… The error which limits republican government to a narrow district has been unfolded and refuted in preceding papers. I remark here only that it seems to owe its rise and prevalence chiefly to the confounding of a republic with a democracy, applying to the former reasonings drawn from the nature of the latter. The true distinction between these forms was also adverted to on a former occasion. It is, that in a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person; in a republic, they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents. A democracy, consequently, will be confined to a small spot. A republic may be extended over a large region.

To this accidental source of the error may be added the artifice of some celebrated authors, whose writings have had a great share in forming the modern standard of political opinions. Being subjects either of an absolute or limited monarchy, they have endeavored to heighten the advantages, or palliate the evils of those forms, by placing in comparison the vices and defects of the republican, and by citing as specimens of the latter the turbulent democracies of ancient Greece and modern Italy. Under the confusion of names, it has been an easy task to transfer to a republic observations applicable to a democracy only; and among others, the observation that it can never be established but among a small number of people, living within a small compass of territory….

On democracy, from Federalist Paper #48:

… In a democracy, where a multitude of people exercise in person the legislative functions, and are continually exposed, by their incapacity for regular deliberation and concerted measures, to the ambitious intrigues of their executive magistrates, tyranny may well be apprehended, on some favorable emergency, to start up in the same quarter. But in a representative republic, where the executive magistracy is carefully limited; both in the extent and the duration of its power; and where the legislative power is exercised by an assembly, which is inspired, by a supposed influence over the people, with an intrepid confidence in its own strength; which is sufficiently numerous to feel all the passions which actuate a multitude, yet not so numerous as to be incapable of pursuing the objects of its passions, by means which reason prescribes; it is against the enterprising ambition of this department that the people ought to indulge all their jealousy and exhaust all their precautions….

Still, many people nowadays believe democracy and republic are just interchangeable terms–meaning, they are one and the same. Well, that is just what the purveyors of democracy would like you to believe. Nothing makes the democracy enthusiast happier than to hear individuals on both sides of the political spectrum refer to our form of government as a democracy. And, quite frankly, it is quite dangerous; and one of the reasons, I believe, the United States has moved so far toward pure socialism.

Granted, the concept and influence of democracy has a long history in the history of American politics, stretching all the way back to the founding of the nation.

The modern Democratic Party was founded in 1828, and traces its origins back to the Democratic-Republican Party organized by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. According to WikiPedia: “The term Democratic-Republican Party is the name primarily used by political scientists for the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republicans.”

The first U.S. president who successfully ran as a Democrat was Andrew Jackson, who served from 1829 to 1837. The modern Democratic Party was formed in the 1930?s from factions of the Democratic-Republican Party.

The term democracy also came heavily into vogue during the Woodrow Wilson Administration, whose famous slogan “making the world safe for democracy” has become a mainstay in the American lexicon. Wilson served two terms from 1913 to 1921. It was around this time that democracy was heavily sold as being synonymous with republicanism and representative government … it has been sold as such ever since.

One constitution where “democracy” appears numerous times is the Soviet Constitution of 1977. Additionally, the term democracy is commonplace in the writings of countless Marxist writers—such as Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Josef Stalin, Leon Trotsky, Antonio Gramsci, and many others. If you would like to confirm this for yourself, visit the Marxist archive at Marxists.org and enter the search term “democracy.”

Granted, Marxian socialists make a distinction between what they call bourgeois democracy versus proletarian democracy, i.e. social democracy. But “democracy is indispensable for socialism,” as Max Shachtman wrote in 1943 in a piece entitled “Trotsky on Democracy and Fascism” (New International, Vol.IX No.7 [Whole No.74], July 1943, pp.216-217).

Another example of the importance direct democracy plays in Marxian socialism appears in the Communist Party of Great Britain’s (CPGB) program from 1951 entitled “The British Road to Socialism.” Section V of the CPGB’s program is titled “People’s Democracy—The Path to Socialism.”

Communism is brought about in stages, and it all starts with pure democracy. Vladimir Lenin once said, “The goal of socialism is communism.” But, as Ivor Thomas wrote in The Socialist Tragedy (1954), there really is very little difference between socialism and communism in practice, despite some of the objections by modern-day Marxist theoreticians to Thomas’ conclusion regarding the ultimate failure of socialism-communism. Pure democracy is a form of collectivism—it readily sacrifices individual rights to majority wishes (a.k.a. mobocracy).

At the close of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Dr. Benjamin Franklin was queried as he left Independence Hall on the final day of deliberation by a woman who asked, “Well, Doctor, what have we got—a Republic or a Monarchy?” Dr. Franklin replied, “A Republic, if you can keep it.”

Related:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lvxaab95pQU

Traitor in Chief will be deal with by Jehovah.