By: Sam Jacobs | Ammo.com

As Venezuela falls into the abyss of economic collapse – the economy has halved in five years, a contraction worse than the Great Depression or the Spanish Civil War – a simplistic narrative in the American press has formed, which starts with the Chavez regime seizing control of the country in 1998.

As Venezuela falls into the abyss of economic collapse – the economy has halved in five years, a contraction worse than the Great Depression or the Spanish Civil War – a simplistic narrative in the American press has formed, which starts with the Chavez regime seizing control of the country in 1998.

(The charismatic populist Hugo Chavez is, after all, the leader most Americans are familiar with when talking about Venezuela, as he made worldwide headlines with his 2006 UN speech where he called U.S. President Bush “a devil” while celebrities like Sean Penn and Michael Moore cheered him on.)

In the 1950s, Venezuela enjoyed its place among the top 10 richest countries on a per-capita basis. How has it turned into a country where more than 2.3 million of its 30 million citizens have fled since 2015 due to starvation? A toxic mix of creeping interventionism, institutional decay, private property seizures, irresponsible fiat monetary policy, and wide-ranging corruption are the main culprits. But Chavez wasn’t the instigator of this mess; the story goes back much further and should serve as a cautionary tale about one country’s faithful adherence to the tenets of socialism to the bitter end.

The Early Venezuela Economy: From Backwater to Boom Country

Gaining its independence from Spain in 1811, Venezuela started out as one of Latin America’s most politically unstable countries, remaining that way until the early 20th century. During this period, Venezuela was primarily a coffee exporter, but the game changed when its first oil field was completed in 1914. From that point forward, Venezuela went from a regional backwater to Latin America’s richest country in a matter of decades.

Oil reserves weren’t the only factor behind Venezuela’s economic success. Property rights were respected, regulations were low, sound money was the norm (Venezuela did not have a central bank until 1939) and the country was able to attract skilled immigrants from Italy, Portugal, and Spain. These factors helped catapult Venezuela to one of the richest countries in the world by the 1950s. Some estimates had Venezuela in the top 10 richest countries on a per capita GDP basis.

Venezuela Transitions into Military Rule

Interestingly, Venezuela was governed by numerous military dictatorships during this time period. Juan Vicente Gómez, who helped consolidate the modern-day Venezuelan state, ruled from 1908 until his death in 1935. Although Gómez had a tyrannical reputation for his suppression of free speech and other basic civil liberties, he did not tamper with the Venezuelan economy. After Gómez’s death, democracy advocates struggled to reform the government for nearly 15 years. Despite the democratic activists’ efforts, Venezuela reverted back to military rule in 1948, under the tutelage of Marcos Peréz Jiminéz.

Under the regime of Peréz Jiminéz, Venezuela received international praise for its economic performance. That being said, the Peréz Jiminéz regime did experiment with certain interventionist policies such as the creation of the state-owned steel company SIDOR and the government’s encroachment into the hospitality industry. But these interventionist policies would pale in comparison to the welfare statism pursued in the following decades.

Enter Democracy and President Rómulo Betancourt

Nevertheless, trouble was brewing. Peréz Jiminéz was no saint and turned to repression to quell opposition to his regime. Peréz Jiminéz’s heavy-handed responses to protests generated a strong opposition movement from leftist activists. It did not help that the business class in Venezuela was also growing weary of Peréz Jiminéz’s spending programs. These factors turned into the perfect storm in 1958. A coup organized by high-ranking military officials and the Patriotic Junta – a political coalition made up of the Democratic Action, COPEI (Christian Democrats), and the Communist Party of Venezuela – succeeded in toppling Peréz Jiminéz.

Nevertheless, trouble was brewing. Peréz Jiminéz was no saint and turned to repression to quell opposition to his regime. Peréz Jiminéz’s heavy-handed responses to protests generated a strong opposition movement from leftist activists. It did not help that the business class in Venezuela was also growing weary of Peréz Jiminéz’s spending programs. These factors turned into the perfect storm in 1958. A coup organized by high-ranking military officials and the Patriotic Junta – a political coalition made up of the Democratic Action, COPEI (Christian Democrats), and the Communist Party of Venezuela – succeeded in toppling Peréz Jiminéz.

Once Venezuela rid itself of Peréz Jiminéz, the country began its transition to democracy. One of the renowned leaders of Venezuela’s democracy movement was Rómulo Betancourt, who eventually became the country’s president in 1959. In previous decades, Betancourt made a name for himself as a left-wing student activist. His political rabble-rousing against then dictator Juan Vicente Gómez would get him exiled from the country. Betancourt was a former member of the Communist Party while exiled in Costa Rica. And although he eventually renounced his Communist approach, Betancourt still believed in a massive state role in the economy.

Betancourt’s socialist lite vision was reflected in the Venezuelan Constitution of 1961, which set the foundation for a vast series of government interventions – labor rights, land reform, and oil industry regulation. In his article, Hugo Chavez Against the Backdrop of Venezuelan History, economist Hugo Faria details the extent of Betancourt’s government interventions:

“One of Betancourt’s first decisions as president was to undertake a land reform aimed at breaking up large landholdings (latifundia). New “owners” of the redistributed land received titles of use, but not full ownership rights. Betancourt’s government established a central planning office called CORDIPLAN, adapted to a mixed economy..

…Betancourt devalued the currency, raising the bolivar price of the dollar from 3.30 to 4.50, and implemented exchange controls. He also increased overall government expenditures, especially consumption outlays. His government tripled the income tax rate, raising it from 12 percent to 36 percent, made the tax more complex, and introduced numerous graduated brackets. Years of successive fiscal deficits made their first appearance and then became a hallmark of Venezuela’s public finance.”

Although Betancourt’s government did not do much damage off the bat, it sowed the seeds for much bigger reforms. These reforms came into fruition in the 1970s, when Venezuela had its first oil bonanza.

The Rise of Petro State Social Democracy

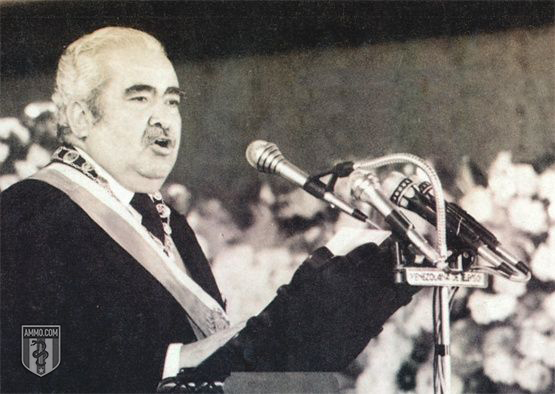

When President Carlos Andrés Pérez came into power in 1974, he ushered in an unprecedented era of government growth. At the time, the world was going through a profound energy crisis, from which Pérez sought to profit. Like any sympathizer of big government, Pérez channeled petroleum rents to finance his extravagant spending program. The nationalization of Venezuela’s oil industry was a crucial step in consolidating Pérez’s vision.

The government did not stop there. Fashioning itself as an all-powerful steward of economic affairs, the Venezuelan government also nationalized the iron industry during the Pérez era. Additionally, the Venezuelan state played the crony capitalist game of choosing winners and losers in the market. Protectionism also became entrenched during this period, as tariffs were placed on a wide array of goods and non-tariff barriers such as import quotas were enacted.

However, no government spending binge is complete without an easy money policy. The Pérez administration made sure to politicize its Central Bank by effectively nationalizing it. From there, Venezuelan politicians had a printing press and a petroleum revenue piggy bank to finance their government largesse.

The Beginning of a Lost Decade

Once the 1980s arrived, Venezuela was drunk on debt and was forced to make several tough calls. Pérez’s successor, Luis Herrera Campins, stated that he inherited a “mortgaged” country.

Once the 1980s arrived, Venezuela was drunk on debt and was forced to make several tough calls. Pérez’s successor, Luis Herrera Campins, stated that he inherited a “mortgaged” country.

And in 1983, the first major domino fell. Venezuela was forced to devalue its currency during Black Friday. Once Latin America’s strongest currency, the Bolívar’s 1983 devaluation opened the floodgates for subsequent monetary malfeasances.

Institutional inertia remained strong in Venezuela as the Herrera administration responded with exchange controls to curtail capital flight. Venezuela’s system of multi-tiered exchange rates would fall under the purview of the “Differential Exchange Rate Regime” (RECADI) agency. Following the Herrera administration, Jaime Lusinchi’s presidency was riddled with scandals. Members of the political class profited off of Venezuela’s exchange rate boondoggle through sweetheart deals and favorable exchange rates that would otherwise not exist in a functioning market economy.

Public outrage and political pressure forced the Venezuelan government to abolish the RECADI exchange control system. However, RECADI’s legacy would be etched in the Venezuelan political economy. It served as an inspiration to the Commision for the Administration of Currency Exchange (CADIVI) and its successor, the National Center for Foreign Commerce (CENCOEX) – two hallmarks of United Socialist Party of Venezuela’s reign throughout the 2000s.

What looked like an unstoppable growth miracle, Venezuela faced its first decade of economic stagnation during the 1980s.

The IMF’s Mixed Bag of Reforms

Like any ambitious politician, Carlos Andrés Pérez re-entered the political scene in the late 1980s. His presidential campaign promised a return to the 1970s bonanza. But once in office, Pérez would be surrounded with several uncomfortable truths. Not only was Venezuela heavily indebted due to its extravagant spending programs, but it was non-competitive at the international level thanks to its protectionist policies. Furthermore, Venezuela’s golden goose, oil, could not bail it out thanks to the low prices throughout the 1980s.

Pérez would immediately turn to the International Monetary Fund for help. The IMF’s suggestions were ultimately a mixed bag. On the positive side, they encouraged tariff reductions and privatization of state-run industries. That being said, the government could not tame inflation, implemented a value-added tax on top of the income tax system, and did not even bother to privatize its state-owned oil company.

Nevertheless, the tariff reductions and privatizations gave the economy some breathing room. But Pérez’s market reforms weren’t without political pushback. In fact, his attempts to restore some semblance of normalcy to the Venezuelan economy would lead to his undoing.

Hugo Chavez and Political Breakdown

Unfortunately, in the middle of these reforms, political drama began to rear its ugly head. Pérez’s own party, Democratic Action (AD), was not a fan of Pérez’s economic program. Fearing that his economic liberalization schemes would undermine their political privileges, they worked tirelessly behind the scenes to stop Pérez’s reforms.

Unfortunately, in the middle of these reforms, political drama began to rear its ugly head. Pérez’s own party, Democratic Action (AD), was not a fan of Pérez’s economic program. Fearing that his economic liberalization schemes would undermine their political privileges, they worked tirelessly behind the scenes to stop Pérez’s reforms.

Additionally, AD had plenty of help on the streets. An assortment of leftist groups took to the streets and protested Pérez’s “austerity” policies. These protests snowballed into the infamous “Caracazo” incident of 1989. In this instance, the Venezuelan government put down a series of protests in the capital city of Caracas, leaving hundreds dead.

Even with this repressive incident, radical groups continued to mobilize throughout the country. One group that stood out was then Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez´s organization, Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200 (MBR-200). Chávez exploited the ever-growing political disarray by organizing an anti-government movement within the Venezuelan military. The MBR-200 attempted to flex its muscles in 1992, with two failed coup attempts.

As punishment for his failed uprising, Chávez was imprisoned. Nevertheless, the damage to the bipartisan model had already been done. As social unrest snowballed, the Pérez administration gradually lost the public’s trust. Pérez’s fate was sealed when he was impeached for corruption charges in 1992.

By then, the Punto Fijo model had completely collapsed. The Venezuela of the 1950s to 1970s – an era of robust growth and political cohesion – soon became a distant memory. The Punto Fijo model then gave way to a new coalition, Convergence (Convergencia), of disgruntled political parties. Headed by President Rafael Caldera, Convergence attempted to reassemble the broken pieces of Venezuela’s political machine.

In terms of policy, Rafael Caldera maintained Venezuela’s statist model of economic organization. Caldera continued implementing certain lukewarm IMF measures, but inflation raged on, peaking at 100 percent in 1996. Structural problems like privatizing Venezuela’s national oil industry were never addressed. Big business’ cozy relationship with the government also remained intact.

No matter how apologists of Venezuela’s democratic era (1958-1998) slice it, its political class delivered sub-optimal results. From 1958 to 1998, Venezuela’s per capita GDP growth was a disappointing -0.13 percent. In essence, Venezuela grew poorer during the Punto Fijo period.

Charles Jones, the author of Introduction to Economic Growth, categorized Venezuela as a “growth disaster” for its lackadaisical economic performance. The only other Latin American country in this economic hall of shame was Nicaragua – a country under the iron grip of a socialist regime and the victim of a bloody civil war.

By the time Chávez entered the political ring, Venezuela was ripe for the taking. Its disillusioned masses were looking for a savior outside of the political status quo, and Chávez fit the bill. At first, Chávez masked his radical Marxist intentions by positioning himself as an anti-corruption candidate.

However, his actions betrayed his neutral rhetoric. Out-and-out Marxists would join Chávez’s brain trust and move him towards radical socialism once in office. Sadly, Venezuela’s fed-up voters were not aware of this when they casted their ballots for Chávez. Unbeknownst to them, Chávez was about to take Venezuela on a dangerous ride.

Chávez was correct in his assessment of the previous Punto Fijo order’s corruption. Unfortunately, he continued the same failed policies, expanding their reach and enacting them in a tyrannical manner. Property rights went out the window once Chávez had full control of the state apparatus. Expropriation of private property became the norm during the Chávez years. According to some reports, the Venezuelan government confiscated upwards of six million acres of farmland. Foreign companies such as ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips also fell on the wrong side of the Venezuelan government’s expropriation crusade.

Chávez was correct in his assessment of the previous Punto Fijo order’s corruption. Unfortunately, he continued the same failed policies, expanding their reach and enacting them in a tyrannical manner. Property rights went out the window once Chávez had full control of the state apparatus. Expropriation of private property became the norm during the Chávez years. According to some reports, the Venezuelan government confiscated upwards of six million acres of farmland. Foreign companies such as ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips also fell on the wrong side of the Venezuelan government’s expropriation crusade.

Economic ignorance continued with currency and price controls, which have caused massive distortions in the Venezuelan economy. In fact, price controls are the main culprit behind Venezuela’s infamous shortage crisis.

Making matters worse, Chávez politicized Venezuela’s Central Bank and state-owned oil company, which were already under too much government influence. State-owned PDVSA was used as a money spigot to finance Chávez’s social spending projects. The Venezuelan Central Bank cranked up the printing press and increased the money supply at astronomical rates. Consequently, hyperinflation is now a reality in Venezuela and is on par with Germany in 1923, the year of Hitler’s infamous Beer Hall Putsch that sought to capitalize on the Weimar Republic’s failed economic policies.

Although Chávez died in 2013, his tyrannical socialist system lives on with his successor Nicolás Maduro. Maduro has continued Chávez’s policy of plundering PDVSA, stripping it of investment, sacking experienced managers, and replacing them with sycophantic military officers.

Even though Venezuela has the world’s largest energy reserves according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the corruption and mismanagement of state-owned PDVSA is symbolic of the larger collapse of Venezuela. In many regards, Venezuela is a failed state and has reverted back to its historical mean – an increasingly fragmented, political backwater.

Long lines to get basic food items. Hospitals running out of medical supplies. Starving people eating zoo animals.

These look like scenes from a post-apocalyptic film. However, these are lurid images of what present-day Venezuela is going through. By opting for the “death by a thousand cuts” route of state intervention in the marketplace, widespread institutional decay, private property seizures, fiat money, and rampant corruption – all pursued in the name of a socialist utopia – Venezuela is bleeding to death from self-inflicted wounds.

One can only wonder how this film would have played out had the Venezuelan populace been armed. Countries like the U.S. have avoided Venezuela’s fate in part due to the presence of armed civilians as a check against would-be tyrants.

If Venezuela had any semblance of a Second Amendment, the Venezuelan people could have stood up against Chávez or Maduro’s tyranny. Human history features repeated episodes of tyrants running roughshod over defenseless subjects, and the Venezuelan case is no different. Political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli was correct in his observation that force is the option of last resort against despots:

“You must know, then, that there are two methods of fighting, the one by law, the other by force: the first method is that of men, the second of beasts; but as the first method is often insufficient, one must have recourse to the second.”

For this tragic chapter of the Venezuelan story to come to a close, the Venezuelan people will have to choose a different path – a path in which property rights and free markets are respected. From there, this horror story will eventually become a distant memory.

Until then, Venezuela is joining South Africa as yet another 21st-century casualty of socialism.

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.